Bloodletting was a bloody misconception

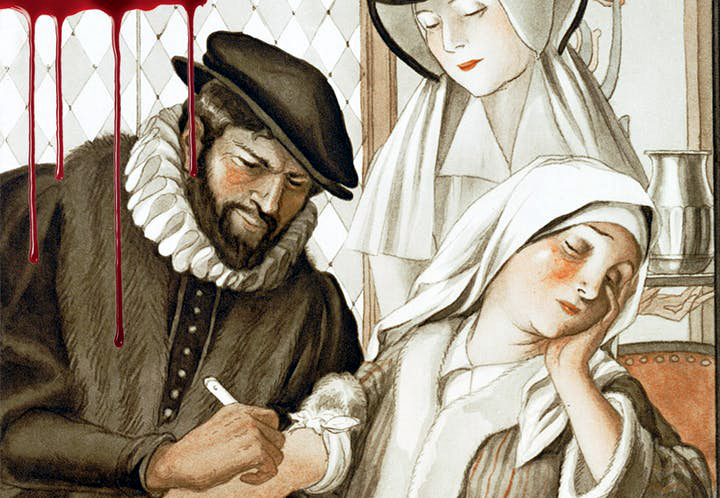

Going to a doctor was the worst thing a patient could do in the 16th century. There was a high chance that his veins would be exposed with a knife. For 2,500 years, blood was drawn from sick people for no reason.

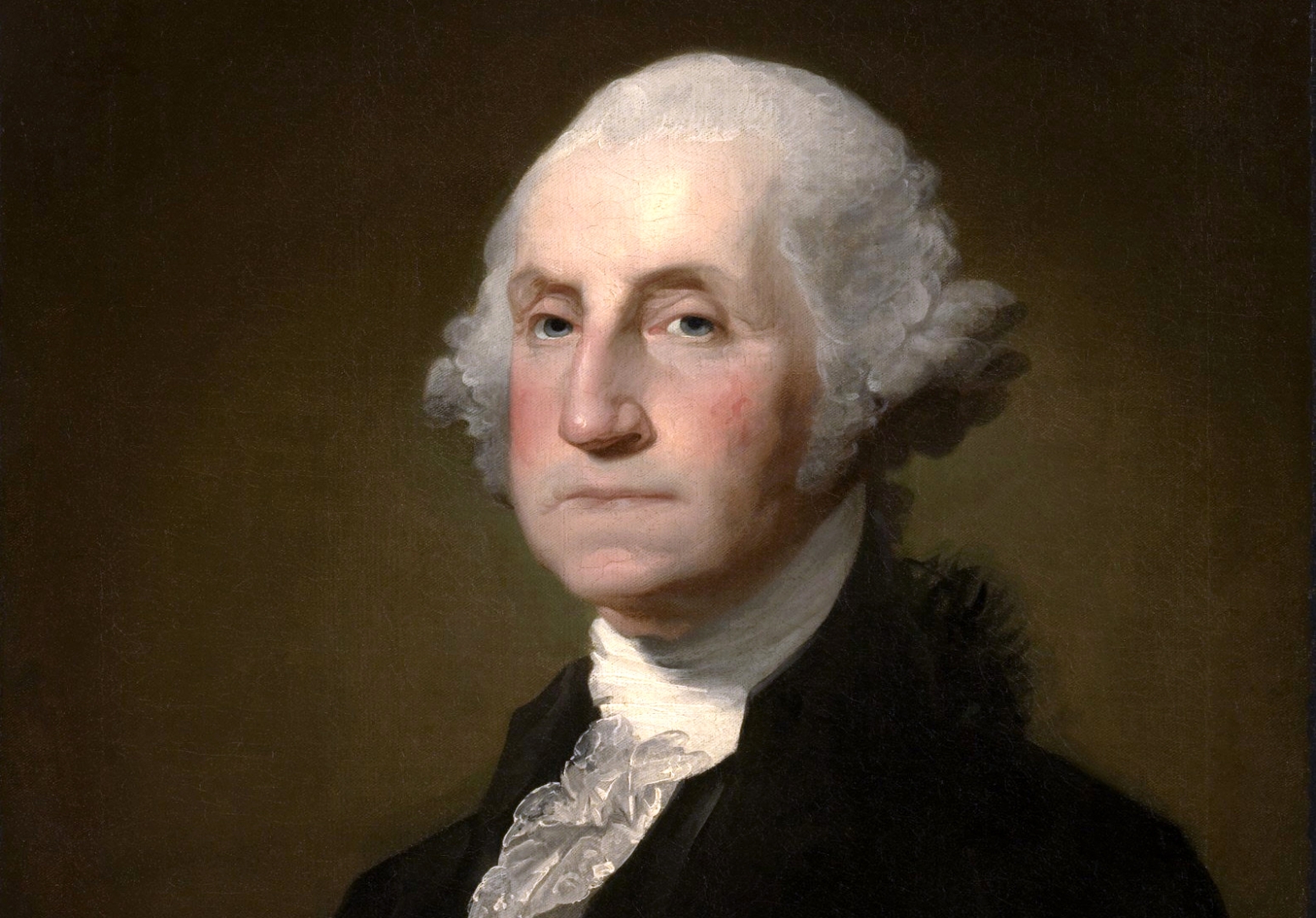

♦ George Washington 1799

On a cold morning in December 1799, George Washington wakes up with a sore throat. In his misery, he does something foolish: he calls for his doctor. After examining Washington, the family doctor summons America's best physicians to ensure that the former president receives the proper treatment. Washington had spent hours driving around in the rain and cold the day before, and the advisory group agreed that he needed to undergo intensive treatment quickly. After discussing the options, they settled on a disastrous treatment that had been considered by doctors for thousands of years as the answer to all ailments and diseases: bloodletting.

Several of Washington's veins are cut open and his blood flows into a bowl on the floor. Because he has a severe throat infection, the doctors decide to drain extra blood. However, Washington's condition deteriorates rapidly. The doctors are surprised by this and decide to drain even more blood.

After a few hours, the doctors have drained no less than 3.75 liters of blood from George Washington, which is about 80% of the total amount of blood in his body.

By evening, Washington is so weak that he instructs his doctors to stop the bloodletting. But it is already too late. A few hours later, he dies.

♦ Body fluids in balance

For centuries, medical science has experimented extensively with all kinds of treatment methods that proved to be inefficient and even harmful to health. And bloodletting took the cake in this regard. Doctors from all cultures and continents endorsed the rationale behind the procedure, despite the fact that it was completely unfounded.

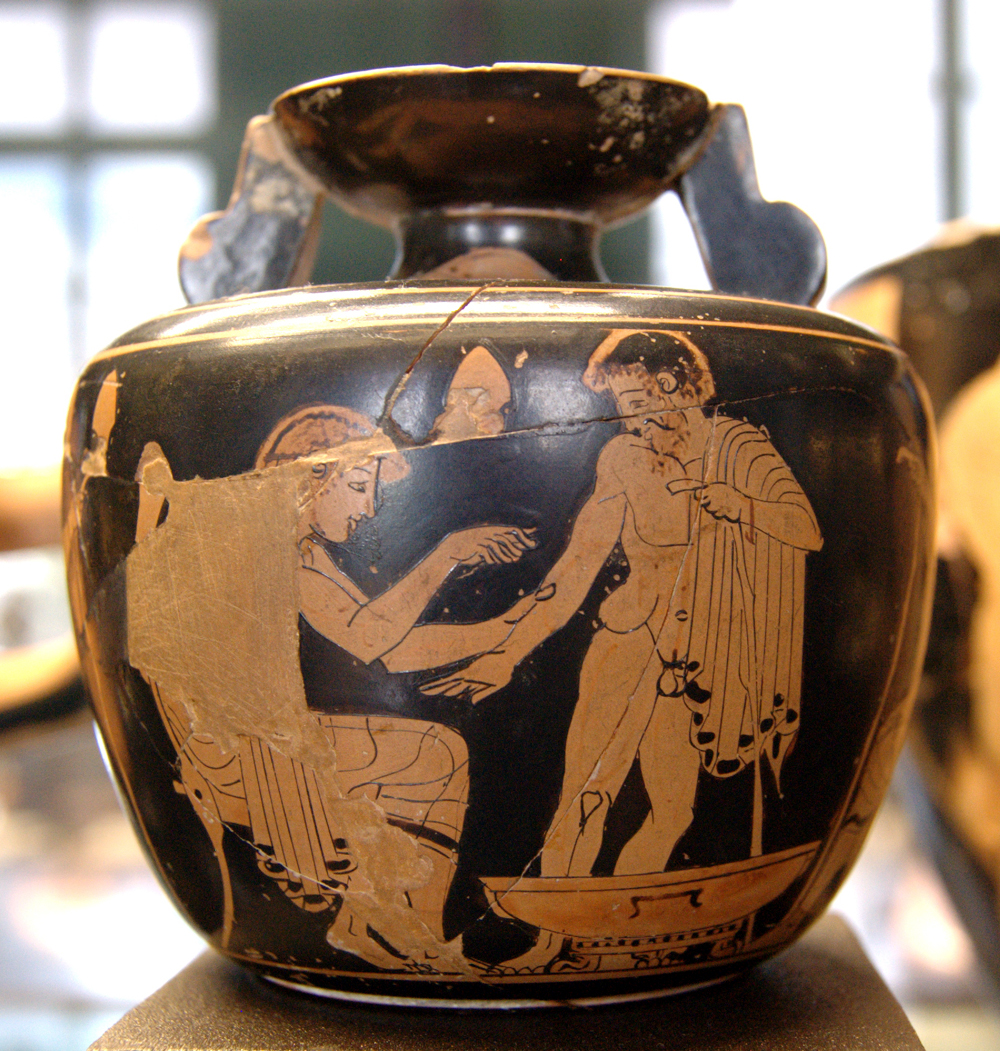

The ancient Egyptians and Greeks were just as fascinated by bloodletting as the Mayans, Aztecs, and Indians.

Christian, Jewish, and Islamic scholars also agreed on its beneficial effects.

Bloodletting can be traced back to at least 500 BC, but probably existed much longer. It remained in use for a very long time: in 400 BC, the famous Greek physician Hippocrates described bloodletting for the first time, and as late as 1923, the treatment was recommended in a leading English scientific work.

♦ The theory behind bloodletting varied from culture to culture.

In Europe, the treatment was based on the ancient belief that you are healthy when your four “body fluids” are in balance.

If you became ill, it was because the balance between the four bodily fluids—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—had been disrupted. Bloodletting allowed you to get rid of the excess of one of those four types of fluids. Because ancient doctors believ

The more serious the illness, the more blood had to be drawn from the patient.

Even when the idea of the four humors was finally disproved, it had no effect whatsoever on the blind faith that doctors had in bloodletting. On the contrary.

A 17th-century English medical handbook lists all the diseases that can be treated with bloodletting, such as cancer, cholera, asthma, herpes, and various mental disorders.

ed that all illnesses stemmed from an imbalance, bloodletting was the answer to almost every problem.

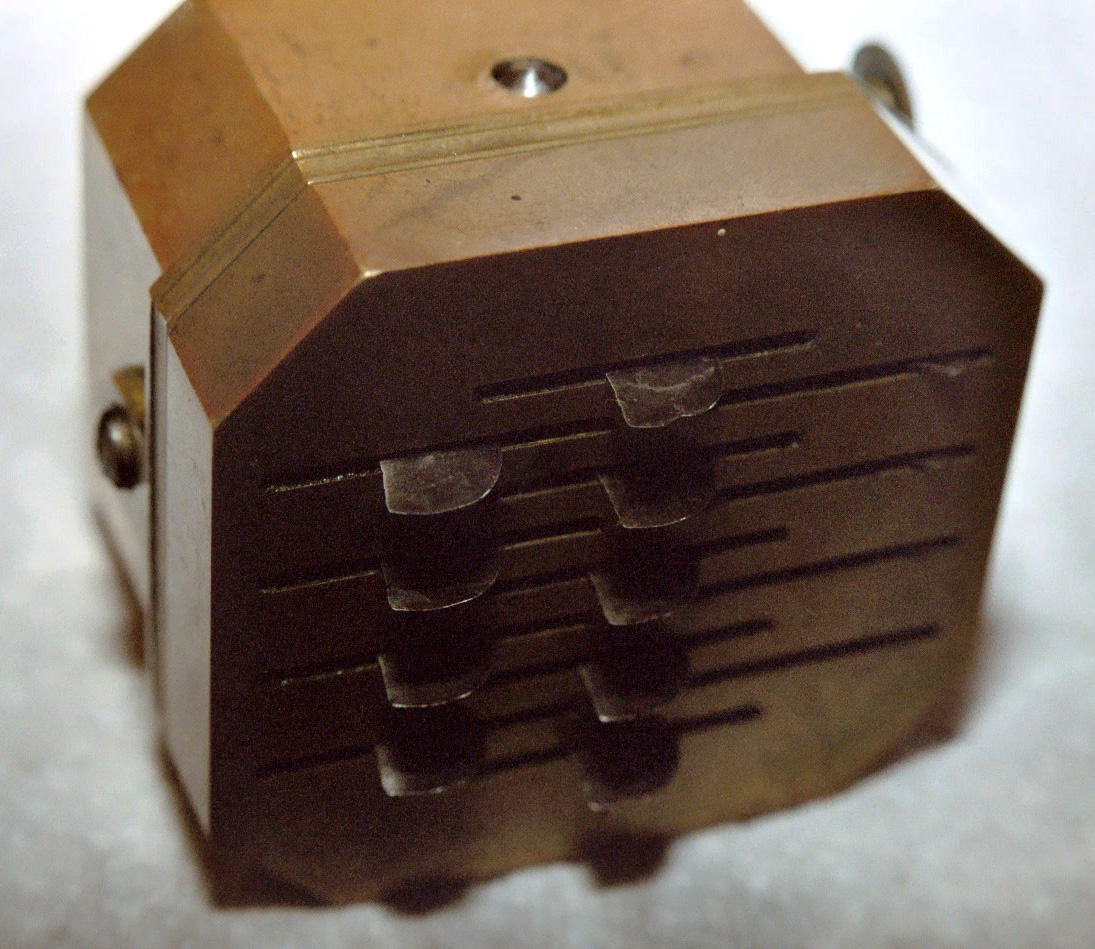

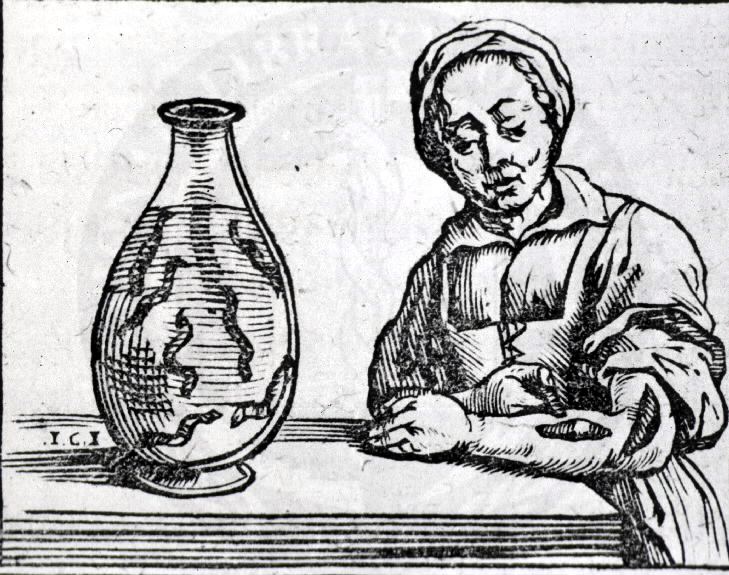

♦ Macabre music box cut veins / Scarificator

In order to perform bloodletting mechanically and quickly, a scary instrument with 8-12 razor-sharp blades was used. In the most commonly used method of bloodletting in the long history of bloodletting, a cut was made in one of the large veins and the blood was allowed to run into a bowl.

In the 19th century, advanced instruments were developed for this purpose. The most frightening instrument was a brass box, known as a ‘scarifier’.

The doctor or barber placed the bottom of the box on the patient's skin. Pressing the release button caused razor-sharp steel blades to shoot out of a small opening and cut through the skin. A mechanism with gears and springs ensured that the blades cut from two different directions and then retracted back into the brass box.

The advantage of the scarifier was that it did not go very deep and therefore only cut open a few small blood vessels in the skin. This meant fewer scars and faster healing. The method was also probably less painful than some other methods. However, the assessment of whether enough blood had been drained from a patient and whether the bloodletting had been effective remained the same: if the patient was unconscious due to blood loss, the doctor was satisfied.

♦ Barber pole symbol of bloody times

Although the symbol for the barber, a pole with red stripes, is found in many Western countries, few people are aware of its macabre meaning.

The red stripe symbolizes the blood flowing from the cuts made by the barber. In addition to cutting and shaving, the barber provided another important service. He also performed surgical procedures, such as bloodletting. The doctor usually only ordered the bloodletting and left the actual procedure to the barber.

♦ Physicians kill the king

It was not until 2000 years later that an authoritative figure spoke out against bloodletting for the first time. English physician William Harvey was the first to discover how the heart pumps blood through the body.

With his knowledge of the cardiovascular system, he proved in 1628 that bloodletting could not possibly be beneficial. His colleagues reacted with suspicion to his discovery and did nothing to disprove bloodletting. William Harvey, who was highly regarded as a physician at the English court, died shortly before Charles II ascended the throne. The death of his skilled physician would prove fatal for the new king.

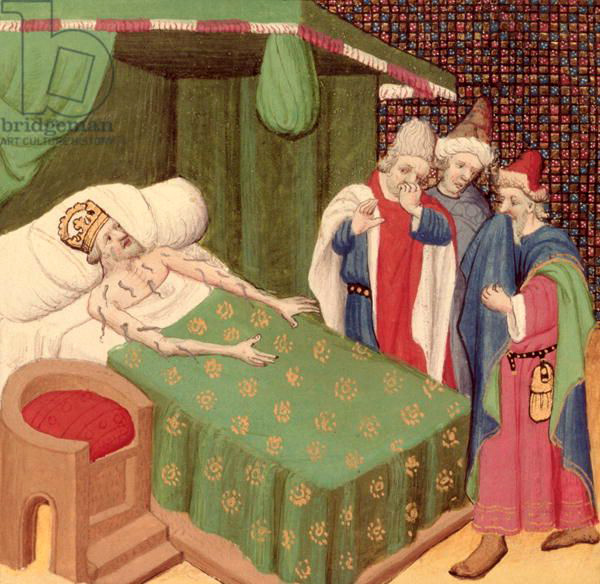

♦ Charles II

Suffered a stroke on February 2, 1685, and urgently needed professional help. Unfortunately, his 14 doctors performed a bloodletting on him. They were well aware of the great responsibility they had and competed with each other over the amount of blood that should be drawn. Although Charles II had already lost a great deal of blood in the first 24 hours, he regained consciousness the following morning. This suggests that he might have recovered from the stroke without further treatment. Unfortunately, his doctors interpreted his recovery as a sign that their treatment had had the desired effect. They therefore saw further bloodletting as the key to the king's full recovery. In the five days that followed, Charles II underwent several bloodlettings, causing his exhausted body to bleed completely dry. In addition, he was given countless enemas and the toxic drug quinine, until the king died after a long period of suffering, finally freed from the torture of his doctors.

♦ The rich were doomed

One of the reasons Europeans were treated with bloodletting for so long is that doctors had few alternatives. Although their knowledge of human anatomy and their diagnostic and surgical skills advanced rapidly from the 17th century onwards, doctors were rarely able to cure their patients. The correct methods for determining the nature of diseases and thus the correct treatments would not be found for a long time to come.

King Charles II's physicians acted on the belief that it was better to apply treatment indiscriminately than not at all. However, they were completely mistaken. It was often better for patients' chances of survival if they were not treated at all. The king's subjects had no idea that poor people were generally better off than the rich and powerful. Those who had no money were not treated by doctors, so they did not run the risk of dying from blood loss and had a chance to overcome an illness on their own.

Bloodletting was used indiscriminately, even when blood loss was the last thing a patient needed.

Medical records tell the story of a French sergeant who was brought into the field hospital on July 13, 1824. He had suffered a serious stab wound to the chest in hand-to-hand combat. Blood was gushing so profusely from the wound that he lost consciousness within minutes. The doctors responded immediately to the severe blood loss. There was no doubt that the sergeant needed acute bloodletting. Half a liter of blood was immediately drained from him to prevent the wound from becoming infected.

The sergeant was severely weakened because he had lost half of his blood. However, the infection had to be treated at all costs, so the doctors used an advanced and effective remedy: leeches.

♦ France bought mountains of leeches

Leeches had been used to draw blood since time immemorial. They were used in addition to opening veins and were placed directly on the area affected by disease. More than 40 leeches wriggled in the blood near the French sergeant's inflamed wound. The use of leeches, each of which can absorb 10 milliliters of blood, about 5 times their own body weight, was very common at the time.

In the 19th century, the use of leeches had become very popular among European doctors. France alone imported around 40 million leeches in 1830. This was mainly due to the Parisian doctor François Brossais. According to him, any illness accompanied by fever was caused by an inflamed organ.

The best remedy consisted of a combination of leeches and bloodletting. The leeches contributed to the French sergeant losing a total of 6 liters of blood during his 6-month hospitalization. According to the standards of the time, this was not an exceptional amount. The most remarkable thing about the whole affair, however, was that the sergeant managed to survive.

Both leeches and bloodletting lost considerable popularity at the end of the 19th century. Major medical breakthroughs, such as the discovery of bacteria, led to better insights.

Although even at the beginning of the 20th century some doctors still stubbornly insisted that bloodletting had beneficial effects, this brought an end to 2,500 years of bloody medical errors.

The Roman emperor Galerius suffered from gangrene, which caused him to smell terrible.

An illustration from Boccaccio's Decameron shows Galerius undergoing bloodletting with leeches. (4th century)

Source: Historia

Bloodletting

References

Source: Historia

Photo's

Wikipedia

Wikimedia Commons

https://nl.pinterest.com/pin/313140980312049605/?lp=true

© Scanpix/Science Photo Library & Shutterstock

Art lijst

Schilderijen

- Bosch, Hieronymus – The Peddler

- Bosch, Hieronymus_The Haywain triptych

- Botticelli, Sandro_Primavera / Spring

- Brueghel the Elder, Pieter – The Tower of Babel

- Campin, Robert — Mérode Triptych

- Courbet, Gustave_The painters Studio

- Dali, Salvadore_The Temptation of Saint Anthony

- Dou, Gerard_the Quack Doctor

- Eyck van Barthélemy_Still life with books

- Fra Angelico_Annunciation

- Géricault, Théodore_Medusas raft

- Magritte, Rene_Prohibited to depict

- Matsys, Quinten_The money changer and his wife

- Memling, Hans_Two horses in a landscape

- Picasso, Pablo_Guernica

- Rembrandt_Abraham en de drie engelen

- Rembrandt_Elsje Christiaens

- Unknown – 16th century: Four depictions of a physician

- Velazquez, Diego_Las Meninas

Schilderijen en de dokter

- Agenesia Sacrale (a rare congenital disorder in which the fetal development of the lower spine)

- Alopecia areata (hair loss)

- Arthrogryposis congenita (birth defect, joints contracted)

- Artritis psoriatica (inflammatory disease of the joint)

- Artritis reumatoïde

- Breast development (delayed)

- Bubonic plague

- Diphtheria

- Eye surgery

- Gigantism and Acromegaly

- Goiter (struma)

- Hare lip (cheiloschisis) / cleft palate

- Herpes zoster (shingles)

- Hunger edema

- Influenza Epidemic of 1858

- Insanity - Malle Babbe (1640)

- Leprosy

- Lovesick, pregnancy

- Lymph node tumor (lymphoma), non-Hodgkin

- Manic Depression Psychosis

- Measles / Rubella? (acute viral infection)

- Melanoma or nevus (birthmark)

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

- Murder (pneumothorax, arterial bleeding)

- Neurofibromatosis

- Osteoarthritis / hallux valgus

- Osteomyelitis

- Otitis media (acute middle ear infection)

- Parotitis (mumps)

- Platvoet en Spitsvoet

- Polio

- Prepatellaire bursitis

- Progeria

- Pseudohermafroditisme

- Pseudozwangerschap

- Psychoneurose (acute)

- Rachitische borst

- Reumatische koorts (acute)

- Rhinophyma of knobbelneus

- Rhinophyma rosacea_depressie

- Rhinoscleroma

- Schimmelziekte_Favus

- Syfilis (harde 'sjanker')

- Tandcariërs

- The Extraction of the Stone of Madness

- Tuberculose long

- Ziekte van Paget

Schilders

Historie lijst

- 1632-1723_Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

- 1749-1823_Edward Jenner

- 1818-1865_Ignaz Semmelweis

- 1822-1895_Louis Pasteur

Wetenswaardigheden lijst

- 1887 Psychiatric Hospital

- Animals on duty

- Bizarre advice for parents

- Bloodletting

- Bloodthirsty Hungarian Countess Elizabeth Báthory (1560–1614)

- Butler escaped punishment three times.

- Dance mania / Saint Vitus Dance

- Doctors’ advice did more harm than good

- French Revolution Louis XVI

- Frontal syndrome (Phineas Gage)

- Heart disease (Egyptian princess)

- Ice Age (minor)_1300-1850

- Ivan IV de Verschrikkelijke (1530-1584)

- Kindermishandeling

- Koketteren met koningin Victoria

- Koningin door huidcrème vergiftigd

- Kraambedpsychose (Margery Kempe)

- Massacre in Beirut

- ME stonden bol van de seks

- Mummie bij de dokter

- Plee, Gemak of Kakstoel

- Prostaatkanker (mummie)

- Sexhandel in Londen

- Swaddling baby

- Syfilis was in de mode

- Testikels opofferen

- Tropische ziekten werden veroveraars fataal

- Vrouwen als beul in WOII

- Wie mooi wil zijn moet pijn lijden

- Zonnekoning woonde in een zwijnenstal